-

Adventures

Posts from our Adventures around the globe.

- Home

- Adventures

Black Canyon of the Gunnison

December 19, 2022Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

Twenty years ago, Congress declared 14 miles of Colorado’s deepest canyon worthy of national park status. If you’ve stood along the edge of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park’s namesake chasm, you understand why—yet the Black is still the state’s least-visited national park. We suggest you go before that changes.

Steep and Deep

Gravity’s pull seems more powerful standing along the rim of Colorado’s Black Canyon of the Gunnison. Maybe it’s the 2,000-plus feet of nothingness, tugging at you from below, that gives the gorge its irresistible magnetism. Or maybe it’s the faint sound of the river that compels you to lean ever farther over the edge. Either way, at 48 miles long, the serrated knife slice into the state’s Western Slope is so dramatic, so vertigo-inducing, so inconceivable in its sheerness that you want to take a step back, you want to look away—but you can’t.

As American canyons go, the Black isn’t the deepest (that’s Hells Canyon in Idaho, at 8,043 feet) or the longest (see: Arizona’s 277-mile Grand Canyon), but no other gully in this country possesses its rare combination of extraordinary depth, verticality, narrowness, and darkness. It is for this reason, and so many others, that in 1999 federal lawmakers elevated the area’s status from national monument to national park, further protecting it from development.

When it comes to national parks, though, 47-square-mile Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park—which encompasses the 14 most scenic miles of the ravine—isn’t widely known. It is, in fact, among the least visited of the nation’s national parks, seeing only 308,962 visitors in 2018; in Colorado, it rides back seat to Rocky Mountain National Park, Mesa Verde National Park, and Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve. There’s little mystery why. A five-hour drive from the closest international airport in Denver and situated well away from major interstates, the Black could generously be called far-flung.

There are other reasons even the most ardent RV driving, iron-on patch collecting, zip-off pant wearing park enthusiast leaves this Colorado destination off his bucket list—namely, minimal infrastructure and inaccessibility. Unlike Yellowstone or Glacier national parks, Black Canyon has zero inside-the-boundaries lodges; the most luxurious setups available in the park are 23 reservable, RV-compatible sites with electrical hookups. That can be a turnoff for those accustomed to a more comfortable outdoorsy experience.

Furthermore, the inner canyon is a designated wilderness area, so there are no maintained trails leading to the Gunnison River at the bottom of the chasm. That in no way suggests visitors can’t get personal with the greenish-blue ribbon of trout-teeming water that, over millennia, carved the Black. What it does mean, though, is that only those with well-above average fitness, route-finding skills, and an abundance of gumption should consider venturing into the depths. Everyone else must be content to roam the North and South rims, taking in the dizzying views either by vehicle or via the handful of along-the-edge walking and hiking paths.

Coloradans, who make up more than 30 percent of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park’s visitors, seem to understand something the rest of America clearly doesn’t: Less is more, especially when it comes to people, roads, cars, and buildings in our wild places. The Black has all kinds of “less.” This first-timer’s guide explains why you should get there before more people figure that out.

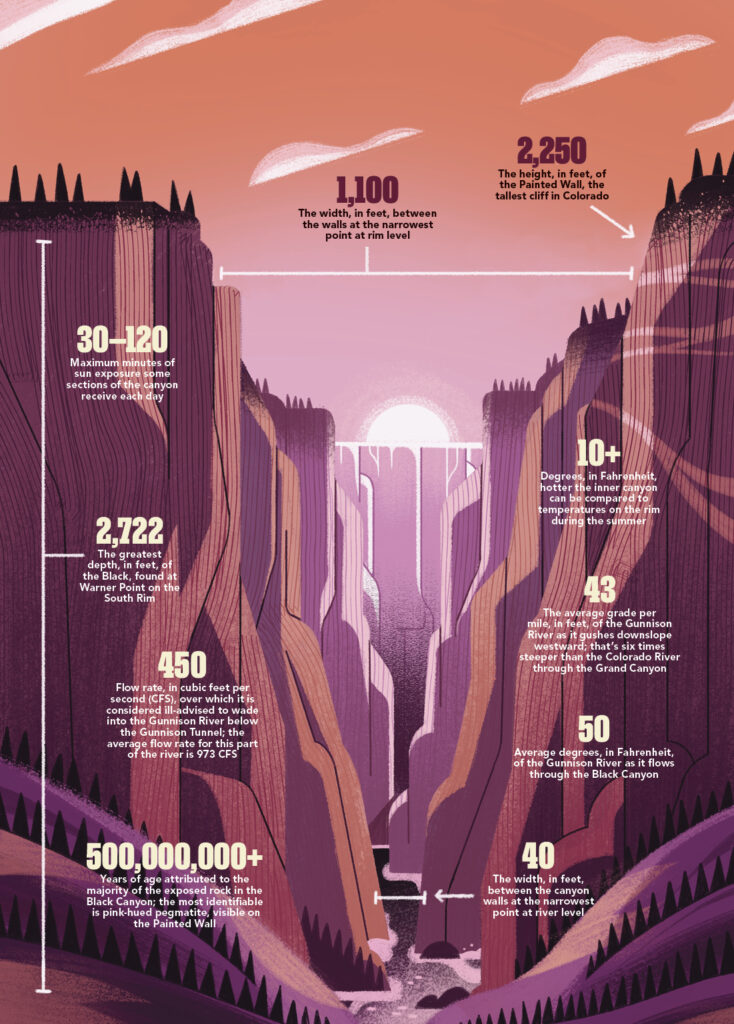

Inside The Black

A by-the-numbers breakdown of Colorado’s most compelling canyon.

History: To Hell And Back

Whether it was at the behest of the railroad companies or in an effort to bring water to arid farmland, early explorers braved the canyon again and again. The Black spat out all but a hardy few.

The Gunnison Expedition

Who: John Gunnison

When: 1853

Mission: Gunnison and Co. were sent by the U.S. military on a crusade to survey a railroad route between the 38th and 39th parallels, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.

Result: The party traveled along the Arkansas River, navigated the rugged Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and crossed the Continental Divide before coming upon what was then called the Grand River and its intimidating canyon. Gunnison (pictured above) wisely declared the gorge impassable and led his team around the South Rim.

For the Record: In what was the first written description of the Black, Gunnison deemed the terrain “the roughest, most hilly and most cut up” he had ever seen.

The Bryant Expedition

Who: Byron Bryant

When: 1883

Mission: The Denver and Rio Grande Railroad hired Bryant to survey the canyon and return with information about whether the company’s line could continue west through the middle and lower stretches of the canyon—and what that might cost.

Result: What was expected to be a 20-day exploration by a 12-man squad morphed into a 68-day slog that only five men had the stamina to complete. Bryant’s final report stated that bringing the railroad through the canyon would be financially disastrous.

For the Record: One of Bryant’s crewmembers, transitman Harvey Wright, wrote of the Black: “Hereto was unfolded view after view of the most wonderful, the most thrilling of rock exposures, one vanishing from view only to be replaced by another still more imposing.”

The Pelton Expedition

Who: John Pelton

When: 1900

Mission: As a resident of the Uncompahgre Valley, Pelton realized the farming community that sustained the mining industry needed more water for irrigation. By the 1890s, plots to tap the Gunnison River via a diversion tunnel were afoot. A team coalesced, and the journey aided by two wooden boats—to find a tunnel location began in the fall.

Result: On day two, one of the boats splintered apart in the rapids, sending supplies into the frigid water. The quest ended after a scant 14 miles.

For the Record: The Pelton party came up with a name for a gushing cascade near where the dejected team escaped the canyon: It was dubbed the Falls of Sorrow.

Torrence and Fellows Expedition

Who: William Torrence and Abraham Lincoln Fellows

When: 1901

Mission: A year after the Pelton Expedition, Torrence and Fellows resumed the probe for a diversion tunnel.

Result: The pair employed an inflatable mattress and rubber bags to ferry their equipment and often resorted to swimming. Their successful trip lasted 10 days. For two more years, Fellows surveyed the river; his work led to the start of construction in 1905.

For the Record: “At the Narrows the fun began,” Torrence wrote. “The canyon is full of great boulders, which form bridges across the stream. Over these we must scramble, one getting on top and pulling the other up. These rocks were slick as grease, and hard to climb. We spent a day in going a quarter of a mile.”

Lay of the Land

Mother Nature took extra care with the Gunnison River Basin, fairly begging Coloradans to protect its treasures. Over time, we have responded, creating conservancies along the waterway, from just five miles west of the town of Gunnison to outside of Delta. The back-to-back-to-back protected zones are an outdoor recreationist’s dream. Here, a primer on the conservation areas that bookend Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park.

Curecanti National Recreation Area

This 43,095-acre park, established in 1965 as part of the Upper Colorado River Storage Project, is composed of three reservoirs, including Blue Mesa Reservoir, the largest body of water in the state. As one might imagine, water-based activities are in ample supply. The surrounding landscape, sculpted by ancient volcanic eruptions and the rushing Gunnison into rugged mesas, plunging canyons, and pointy spires, offers plenty of dry fun, too. Hiking, horseback riding, birding, camping, and small- and large-game hunting are all on the menu. Where Curecanti ends, two miles below the Crystal Dam, the national park begins.

The Drive-By

More than 20 scenic overlooks inside the national park offer the easiest ways to experience the canyon’s grandeur.

Although the pine-log fencing and stone stanchions look sturdy enough, visitors tend to approach them with a certain level of apprehension at first. As well they should. Almost all of the 20 or so scenic overlooks in Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park allow visitors to inch their ways right up to the precipice, a position that simultaneously makes one feel like she is flying and falling.

For the vast majority of parkgoers, spending a day driving along South Rim Road—stopping at the visitor center and spots with promising names like Devils Lookout, Chasm View, and Painted Wall View (pictured)—is what visiting Black Canyon is all about. That is, of course, no different from how huge percentages of visitors experience Arches National Park in Utah or Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming or Redwoods National Park in California: Sightseers drive from arch to arch or from geyser to geyser or from big tree to big tree, usually in a line of cars.

Black Canyon rarely sees bumper-to-bumper traffic (note: July has the highest numbers) along the paved South Rim Road; however, the secret that even park rangers don’t want to share is the relative solitude of the North Rim. In July 2018, more than 46,600 people stopped at the South Rim visitor center, while only 1,282 parkgoers checked out the North Rim. Because there is no bridge over the canyon, accessing the North Rim requires a bit of a drive. You’ll need to allow two to three hours’ drive time from one rim to the other—but it’s entirely worth it. Not only are there far fewer people, but the views from the North Rim are also more dramatic, if that’s even possible.

Q&A:

If you like to…cross-country ski and you like the whole walking in a winter wonderland thing, you can park at the visitor center and then slip-slide your way for six miles on the groomer-for-skiers South Rim Road, but keep in mind that winter temps can be downright frigid; weather can roll in quickly; and there are no places to take shelter should you be unprepared for the worst.

If you like to…ice climb and you like beautiful views, too, you can try either Gandalf’s Beard, a two-pitch climb east of Chasm View overlook, or Shadowfax, a two-pitcher located off East Portal Road, but keep in mind that Gandalf’s Beard has failed to fully materialize for the past several years; call the visitor center for up-to-date information just in case the wizard has, once again, been delayed.

The Car-Camping Chronicles

Most people who plan to overnight inside the park stay in one of three locales—the South Rim, the North Rim, or the East Portal campgrounds. In the summer, most of the South Rim’s 88 campsites are reservable via recreation.gov ($16 to $22 per night, plus a $3 reservation fee). The 15 sites ($16 per night; no RVs) at East Portal and 13 sites ($16 per night) at the North Rim are first come, first served and close seasonally. These RV- and tent-laden settlements are much like those in any other national park; however, the difference between being at the Black and being at a campground in, say, Rocky Mountain National Park is the relative isolation. From South Rim and East Portal, it’s a 30-minute drive to the closest big-box grocer; from the North Rim, it’s 40 minutes. In short: Knowing what you need before you arrive is key.

1. Set Your Sites

The South Rim

Open year-round, the South Rim Campground has three loops, each with its own set of regulations. All 88 sites accommodate tents and/or small RVs. A Loop has several sites for medium-size trailers, and reservations are accepted. B Loop makes room for larger trailers, takes reservations, and has electrical hookups in the summer. C Loop is first come, first served and only accommodates small RVs. Generators throughout are a no-no. Reservations must be made at least three days in advance. Dogs on leash are generally allowed in all park campsites, but visit Black Canyon’s website for specific rules. Best sites: A31, B23, and C18.

The North Rim

This campground is typically open from April to mid-November and has 13 sites. All sites accommodate tents; RVs are allowed, but sizes greater than 35 feet are not recommended and there are no hookups. Generator use is allowed during designated times. All sites are first come, first served. Best sites: 1 and 4.

The East Portal

Sites here are usually open from May to mid-October; the campground has 15 sites. All sites are first come, first served and accommodate tents; RVs are prohibited. Best sites: Any spot in the lower tier, away from the entrance station.

2. Light My Fire

All campsites are equipped with fire rings with grilling grates, but campers must bring their own firewood. Collecting wood—dead or alive—inside the park is forbidden. Campfires outside of fire rings are prohibited.

3. Table Service

Each site has a wooden picnic table, but we suggest bringing comfortable camp chairs for around the fire ring.

4. From the Tap

Water is generally available in all three campgrounds from mid-May through mid-September. RV-filling is not available.

5. Bear Prepared

Bears roam the Black. Place all “smellables”—food, scented toiletries—in the bear boxes or lockable dumpsters at night.

6. Nature Calls

All Black Canyon campgrounds have vault toilets, (usually) supplied with toilet paper. But you might want to bring an extra roll, just in case.

7. Zero Bars

You’re in the great outdoors, people: Don’t expect cell service.

8. Look Up

The Black was designated as an International Dark Sky Park in 2015. The classification means the park offers exceptional star viewing because of the area’s minimal light pollution. Mark your calendar: The park is hosting an astronomy festival, with guest speakers and special activities, from June 26 to 29.

Visitor Center: The South Rim visitor center is open every day except Thanksgiving and Christmas. Summer hours are generally between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. Offseason hours are typically from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Now I see the secret of making the best person: it is to grow in the open air and to eat and sleep with the earth - Walt Whitman

This Now I see the secret of making the best person: it is to grow in the open air and to eat and sleep with the earth - Walt Whitman